I’m internally conflicted about punk. Its abrasive, bile-spewing nihilism is compelling; its wilfully obstreperous lack of melody and musicianship less so. I want to like it, but I can’t entirely, because it’s insufficiently pretty. Obviously, there’s a link between the ugliness of the music and the acidity of the Geist, but I would contend that malcontented misanthropy can be channelled with more tunefulness than most of the original punk acts were willing or able to marshal. I like plenty of loud bands, from Alice in Chains to Nine Inch Nails, but, in my opinion, certain barely perceptible, but appreciable and critically important, pop structures underpin even Trent Reznor’s most raucous this-is-the-sound-of-my-arm-in-a-food-blender industrial death march. Such structures are conspicuous by their absence in most of the 70s punk stuff, hence my ambivalence.

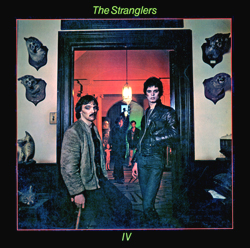

But what of the Stranglers? A curious proposition indeed, and one that frequently goes under the radar when people talk about the origins of punk. They were formed in 1974, and are perhaps most famous for “Golden Brown”, their harpsichord-driven, heroin-addled smash hit from 1981. But the mock-Tudor tweeness of their signature song belied the fact that the Stranglers were purveying pared down, in-your-face pub rock before the formation of the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, or the Clash, and there’s little doubt that they prefigured the abrasive and confrontational spirit of the second half of the 70s.

Yet the Stranglers are rarely accorded the same historical significance as any of these punk luminaries, and there’s little evidence that they exercised much of an influence on the burgeoning punk movement. Why? My opinion is that they fell into the gap between glam and punk; too dour for the former, their musicianship too accomplished for the latter. For indeed, the Stranglers could actually play their instruments, which was considered unforgivable amidst the do-it-yourself discordance of the late 70s, and most objectionably of all, their lineup featured a keyboardist. Shocking.

On the whole, the Stranglers’ sound was more pre-punk than punk, and heavily reminiscent of the gritty, unpolished art-rock of the Velvet Underground, right down to the seedy and transgressive lyrics. Certainly, their debut album Rattus Norvegicus is one of the nastiest records I’ve listened to in the process of writing this blog. Not over-the-top, schlock horror nasty, like some embarrassing Norwegian death metal act, or even performatively histrionic, like the swastika-sporting Sex Pistols, but merely riven with a kind of low-key, deeply provincial mean-spiritedness. Unreconstructedly sexist, xenophobic, thoroughly uncharitable sentiments pepper the album from beginning to end, and there’s barely a good-natured or conciliatory moment to be had throughout its 40-minute duration.

Most striking is the all-pervasive and occasionally uncomfortable air of misogyny. The album opens with “Sometimes”, a rumbling, bad-tempered, bass-heavy rocker with a frenetic keyboard and lyrics about, if I’m not mistaken, Hugh Cornwell wanting to beat the living shit out of his girlfriend. “London Lady” eases off on the violent intent, but it’s equally as vituperative, launching a ladle of poison at one of Jean-Jacques Burnel’s ex-flames, a busted up, plastic surgery-enhanced hack who has, it seems, got nothing to “look so pleased about”. “Princess of the Streets”, meanwhile, is an over-the-top slice of cartoonishly maudlin lovesick punk about being dumped by a woman who is “real good looking”, but who is, equally, “no lady”, and who will “stab you in the back” given half the chance. The song’s chorus charmingly describes this femme fatale as “a piece of meat”.

This kind of thing was very much of its time. As many of the earlier reviews on this blog indicated, a lot of the early 60s and 70s rock’n’roll records evinced some discomfortingly incorrigible takes on the fairer sex. The Madonna / Whore dichotomy, the female presented as both all-powerful deity and denigrated sack of shit, sometimes in the same song, was central even to the sacred texts of Their Holinesses Lennon and McCartney, most notoriously “Run for your Life”, Rubber Soul’s terrifying closer. And indeed, some fifteen years after the release of Rattus Norvegicus, Guns N’ Roses could still sell thirty million records despite around half of Appetite for Destruction thematizing Axl Rose’s proclivity for giving unfaithful and disobedient harlots a well-deserved knuckle sandwich.

And yet, even amidst this vaunted company, the No Platform-worthiness of Rattus Norvegicus is striking. Astonishingly, “Peaches” was one of the Stranglers’ biggest hits, even though it’s very obviously about a trench coat-wearing pervert patrolling the promenade in summertime and ogling the semi-naked women on the beach. “Liberation for women, that’s what I’m preaching”, proclaims the gleefully malignant Cornwell, in an interesting nod to the idea that the ostensibly progressive sexual revolution of the 60s played into the hands of predatory males, who suddenly saw the menu get a lot bigger, almost overnight. “Ugly”, meanwhile, is perhaps the most obnoxious moment on the record, a disjointed, rambling diatribe which sees Burnel strangle his girlfriend after she attempts to poison him, express his disdain for ugly people, and then meditate on how old men can still get girls if they’re rich, especially if they’re Jewish. Oh dear.

When the album does depart from this bargain basement fascism, the subject matter isn’t much cuddlier. Urban decay and the disorientating directionlessness of modern life in big cities were key themes of 70s rock, and the Stranglers inevitably stick their ores in here as well. But they neither celebrate the sleazy anonymity of city life, as many of the glam acts did, nor do they essay a naturalist, Kinks-style denunciation of its depravity. Instead, they merely describe it, with icy precision, and in the weirdest and most acerbic ways imaginable.

“Hanging Around”, perhaps the album’s highlight, describes various lost souls of the urban landscape – wannabe groupies at gigs, hustlers on the streets, leather glad weirdos in S&M clubs – as simply “hanging around”, aimlessly trying to pass the time in Sodom and Gomorrah through the pursuit of pointless pleasure. “Goodbye Toulouse” is a brief, baffling slice of punk about Nostradamus’ apocalyptic predictions for the French city of the same name. And the album’s closer, “Down in the Sewer”, is stranger still; a discordant, proggy, eight-minute punk rock opera, written from the perspective of a rural rat which leaves its cosey and cosseted life on the farm to live in the city and breed with the bigger, more dangerous vermin of the sewers. This new, elite race of super-rat “will be called survivors”, a further reflection of the brutal, dog-eat-dog (or rat-eat-rat) Darwinism which underpinned the ideology of much of the punk movement.

Indeed, perhaps the only somewhat human moment on Rattus Norvegicus is “Get a Grip On Yourself”, which was written before the Stranglers were signed, and which relates the poverty, precariousness, and frustration of life as an aspiring, socially marginalised rock musician. Even here, the sound is jagged, uncompromising, interspersed with Dave Greenfield’s deranged keyboards and transgressive lyrics about being committed to a mental asylum for “crimes against the soul.”

Overall, then, Rattus Norvegicus makes for an unpleasant listen, and raises the question of what the hell was in the air in mid-70s Britain to produce this level of cynicism and viciousness. And yet, the Stranglers’ contribution to the very particular darkness of this decade was not wholly of a piece with the operatic biliousness of punk. Instead, we’re dealing here with a low-key misanthropy, a kind of quiet, provincial fascism, perhaps the feintest murmur of the cold-hearted, Darwinist neo-liberalism which would come to dominate Britain in the 1980s, after the cleansing fires of punk had been quenched and its noxious spirit had, along with Johnny Rotten, “crossed over into free enterprise”.

Overall rating: * * *

Standout tracks: “Sometimes”, “Hanging Around”