Bryan Ferry – surely one of the biggest prats in the history of rock – actually comes from oop North, the son of a farm labourer, a scion of the uncultivated and unreconstructed black pudding-eating proletariat which, in the 1970s, was spawned in dark Satanic furnaces everywhere north of Watford, like the Orcs of Isengard. The big tart spent the proceeds of his paper round on jazz magazines, studied fine art at college, and ultimately transitioned into the thinking man’s lounge lizard, as lead singer of avant-garde glam rock miscreants Roxy Music, alongside his partner in crime Brian Eno, the legendary and exceedingly bald mastermind of self-congratulatorily strange 15-minute-long ambient marathons which you will almost certainly have heard, if you watch many documentaries about the Great Barrier Reef.

The two Brians indeed. To my mind, it’s a supreme irony that destiny chose to adorn Ferry, this purveyor of cutting-edge synth-infused jazz rock, this enigmatic mishmash of Roger Moore and Marc Bolan, this impeccably dressed Casanova, who rarely turns up to an interview unsuited or unbooted, with the singularly square and unwieldly monicker Bryan. Owch. He surely despises his parents for inflicting it upon him – it’s the name of a solid, dependable, 52-year-old bricklayer from Doncaster, not of an auteur who, amidst the consuming smog of 1970s trade union-dominated Britain, single-handedly sought to channel the suave, stylish, decadent spirit of Weimar Berlin, and actually managed to get himself on the radio in the process.

And yet Bryan is not a prat, for according to the dog-eared dictionary close to my desk, the definition of “prat” is someone “incompetent” or “lacking talent”. Only the most po-faced detractor of 70s glam, the most insufferably bearded disciple of proletarian, meat-and-potatoes, guitar-shagging authenticity, would describe Bryan Ferry as “lacking in talent”. Like his contemporaries Bowie and Bolan, Ferry emerged out of the ashes of, and ostentatiously rejected, the spirit of the 60s. In opposition to the earthy, unaffected, communitarian elan of “classic rock’n’roll”, 70s glam was emptily, but unashamedly, materialistic, mercurial, and self-consciously theatrical – mere spectacle designed to shock and, most importantly, to sell.

But even by the freakish and provocative standards of the Wacky Races-style cartoon landscape of the early 70s, Roxy Music stood out among their big haired, blouse-wearing, airheaded contemporaries. They were aloof, elitist, their artsy-fartsy sound opaque and unapproachable, their lyrics strange and sometimes about falling in love with inflatable sex dolls on country estates. Initially, they half-heartedly aped the glam look, wearing glitzy blouses and leopard print tights, but it soon became apparent that Ferry, the uppity art school sophisticat, was never really into this kind of trendy adolescent gender-bending, and as the 70s wore on, he swapped the makeup and shimmering frocks for the austere, unmistakeably masculine three-piece suits which remain his hallmark.

Bryan Ferry, then, is something of a Thatcherite phenomenon, a kind of reverse Damon Albarn; a working class lad from county Durham who transcended his humble origins, graduated into the upper-middle-classes, made difficult, challenging music which confounded the hoi polloi, put on a tuxedo every time he went to Waitrose, and regularly drank champagne with minor royalty at exclusive parties in the Southeast of England. By the end of the 70s, acid-tongued hacks in the British music press had dubbed this class traitor, this feudalised petit bourgeois, as “Byron Ferrari”, and inevitably, such a figure proved an irresistible target for the gleefully malignant and trigger-happy upstarts of punk. Johnny Rotten and Vivienne Westwood despised his effete twattery, and they put Ferrari on a long list of people they hated, alongside Rod Stewart and Mick Jagger.

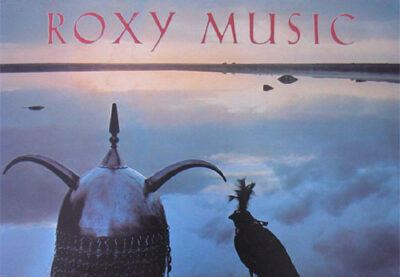

Judging by Avalon, though, Bryan didn’t give a toss. This was Roxy Music’s final record, released in 1982, long after the acidic tide of punk had abated, and from listening to it, you wouldn’t know that the Sex Pistols had ever even existed. If anything, it’s more accessible, more poppy, less arty and discombobulating than Roxy’s early 70s output, and it is utterly, almost defiantly untouched by the rage, crassness, or directness of punk. Its sound is refined, ethereal, non-confrontational; the definitive anti-punk record written at a time when the embers of punk were still glowing amidst the blackened coals of rock, refusing to die.

Avalon is a pop record, and a glacial one at that. The bass is prominent, occasionally funky; the synths can be intrusive; sometimes the pace picks up a bit. Overall, though, the album never really rocks out or leaves first gear. It remains staid, subdued, suggestive almost from start to finish, like a languid summer dream. Actually, it’s a fascinating, almost cinematic sound that Ferry conjures here, a stately, subliminal variation of synth-rock to which some wits have attached the term “sophistipop”. This combination of rock, pop, and ambient electronica is reminiscent of other classic albums of the time, such as Peter Gabriel’s So or Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love, but the sound on Avalon is less sharp, more homogenous, strangely hypnotic and absorbing, with each song melting imperceptibly into the next and none of them too conspicuous, with a couple of exceptions.

One such exception is the opener, “More Than This”, a brilliant slice of eerie 80s dreampop, later given the mass exposure it so richly deserved by Bill Murray’s tense serenading of the devastatingly attractive Scarlett Johansson in 2003’s Lost in Translation. But what is the “this” that there is “nothing more than”? Unfortunately, this question brings me to the part of the review where I am required to comment on Avalon’s lyrical themes. This is challenging because, from what I can tell, the lyrics are – if we’re being generous – cryptic, inscrutable, and targeted largely at the subconscious mind of the listener, and – if we’re not – arch gibberish.

But let us nonetheless try to divine the meaning behind Byron Ferrari’s musings. Unless I’m very much mistaken, most of Avalon is about sex. The “this” in question is, I assume, getting laid, or at least being romantically wined and dined by, presumably, Bryan himself. “The Space Between” and “The Main Thing” are similarly, subtly sultry; jazzy, danceable pop songs dominated by irresistibly funky basslines, but with ominous synths and ghostly vocals which render both unexpectedly foreboding. In the former, Bryan implies that only physical intimacy can repair the glaring gap that has developed between himself and his lover, while the latter makes sparse references to a “soul on fire” and “burning with words of sand”. The eerie and beautiful title track is equally erotic; it seems to be about Bryan drunk and sleepy at a Great Gatsby-style knees up, until some sassy minx steps in and drags him back to the dancefloor, reinvigorating his libidinal lust for life through the power of Samba, and perhaps Viagra.

But when Bryan’s soul isn’t on fire because of some pretty piece of flesh, he’s heartbroken and pining, like an overgrown teenager. After an interminable intro, “Take A Chance With Me” is an exceptional piece of 80s jangle pop, and one of the few moments where the album’s pulse picks up a bit. Its lyrics, however, are soaked in a most unbecoming self-pity about how “too much love made me sad”, and how, though “people say I’m just a fool”, they should “learn to love me the way I do.” The prick teasing jezebel who got Bryan into this embarrassing state is also, presumably, the addressee of “To Turn You On”, a dirty, distressed love letter written to someone on the other side of the world (“Who cares about you except me? God help me”). The on-going mid-life-crisis continues apace on the droopy, saxophone-powered “While My Heart Is Still Beating”, which sounds more David Bowie than David Bowie, and which finds Bryan plaintively asking if his heart will ever “stop bleeding”.

Overall, then, Avalon trades primarily on a distressed, slightly sinister sounding erotica; forbidden or toxic sex as a way of briefly gaining access to a state of momentary bliss. Come to think of it, this is precisely what the term “Avalon” refers to – a mythical realm of winged horses drinking from clear blue lakes, a paradise delivered from all suffering and conflict. Love is the drug, and when it isn’t forthcoming, Bryan gets sad, grumpy, and surprisingly needy, for a member of the Chipping Norton set. But the question of how real any of this is lingers; the entire album sounds like a deep, dark, sensual, sad dream, a strange, lascivious miasma. This abates only on the closing track, the appropriately named “True to Life”, a moment of detached, contemplative, fully awake and individuated loneliness, a sudden confrontation with the cold, banal reality of being a millionaire rockstar.

* * * *

Standout tracks: “More Than This”, “Avalon”, “Take A Chance With Me”