Continued from part I.

Pin Ups (1973)

I’m hesitant to include Pin Ups in this deep dive. It’s a collection of cover versions, in which Bowie takes songs that were inspiring to him as a teenager in the mid-60s, and renders them in a glam or even pre-punk style. The album was hastily thrown together to fulfil some contractual obligations and get RCA Records off Bowie’s back while he completed Diamond Dogs, the follow-up to Aladdin Sane, and given this tight schedule, it’s a surprisingly well-executed album. But that doesn’t save its sorry ass, unfortunately. My issue is not with the sound, but rather with the source material, because almost all of the songs featured here comprise risibly simple-minded mid-60s Baby Boomer garage rock, complete with the usual childlike boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl lyrical idiocy. The closing songs venture away from Happy Days-style lovesickness and toward more thoughtful work by the Kinks and the Who, but it’s too little, too late, unfortunately. Most tragic of all is that Pin Ups was the last time Bowie would work together with Mick Ronson – a veritable wet fart of an ending to their storied and highly productive bromance.

Overall rating: *

Standout track: “Sorrow”

Diamond Dogs (1974)

Diamond Dogs represents an unwieldy fusion of several disparate and ill-fated artistic projects in which Bowie had become embroiled; writing a follow-up to Aladdin Sane, turning Ziggy Stardust into a musical, and adapting George Orwell’s 1984 as a theatre production, all while succumbing to the influence of William S. Burroughs’ apocalyptic imagination. The resulting record is even less musically and conceptually cohesive than the notably scattered Aladdin Sane. Across six minutes of gnarled, sprightly Rolling Stones-style rock, the opener and title track sketches a dystopian scenario of teenage gangs prowling a smouldering urban landscape in the wake of a nuclear war. Yet both this idea and the musical style soundtracking it are swiftly jettisoned, as the album flies off in unexpected directions. “Sweet Thing” is a touching ballad written from the perspective of a male prostitute; “Rebel Rebel” an uncompromising transgender anthem and Bowie’s final flirtation with glam; while “Rock’n’Roll With Me” is a Meatloaf-esque power ballad about the pressures of fame. The closing songs then abruptly set key moments from 1984 to, variously, eerie Doors-esque organ music, string-laden soul, and grandiose art rock. Every track on Diamond Dogs is very good, but taken together, it makes for a somewhat disorientating listen.

Overall rating: * * * *

Standout track: “Rebel Rebel”

Young Americans (1975)

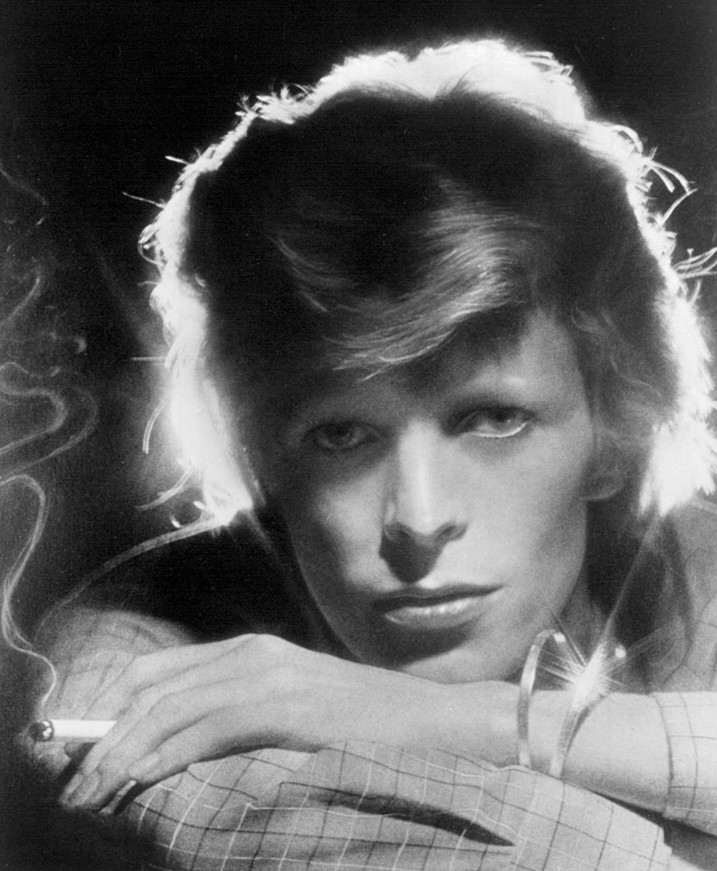

After a world-bestriding intergalactic rock opera, a collection of covers, and two deranged glam extravaganzas, it only stands to reason that Bowie would confound all expectations (and, of course, grandly and self-indulgently demonstrate his artistic unpredictability) by moving to LA and recording a soul album, which is precisely what he did with Young Americans. Even the first impression is instructive – after the subversion and grotesquery of the cover art on the three preceding records, Bowie suddenly appears as fresh-faced and unmistakeably terrestrial, smiling warmly and smoking a post-coital cigarette. For once, he carries the album’s central idea across its duration, with eight tracks of saxophone-infused R&B, complete with soulful Motown backing vocals and phat, funky beats. Nonetheless, this is Bowie, so it has to be somewhat sinister; the songs deal with drug addiction (“Fascination”, “Right”), fame, fame, fatal fame (“Somebody Up There Likes Me”, “Fame”), and the self-absorption of “Young Americans”, who live in the eternal present of Christopher Lasch’s “Culture of Narcissism” (“do you even remember yesterday?”) Yes, Bowie appears here as a besuited crooner – but he’s a ghostly hologram of one, singing in the deserted music hall of a spaceship headed for the sun.

Overall rating: * * *

Standout track: “Fame”

Station to Station (1976)

After the cocaine-fuelled high of Young Americans comes the drug-induced psychosis of Station to Station. By this point, Bowie was rarely leaving his LA apartment, where he spent his time taking industrial quantities of Columbian marching powder, reading books about the occult, watching documentaries about the Third Reich, and storing his bodily fluids in small jars in the fridge, to obviate the risk of “demonic possession”. This rather alarming set of circumstances birthed his final alter ego, an inhuman, fascoid aristocrat known as the “Thin White Duke”, with Station to Station essentially serving as a vehicle for the character’s presentation. Musically, it could be considered a transition between the funky soul of Young Americans and the dour, synthesiser inflected art rock of the Berlin trilogy, but overall, this is a meandering, erratic, solipsistic record, characterised by odd musical structures and opaque lyrics. It kicks off with the thoroughly mental ten-minute title track, which culminates with Bowie intoning “the European canon is near” over thundering pianos, and it includes an unexpected plethora of achy love songs, most notably a rather beautiful rendition of “Wild is the Wind”. To characterise this as a “cocaine record” would be a massive understatement; it’s perhaps the maddest item in Bowie’s discography, which is saying something.

Rating: * * *

Standout track: “Wild is the Wind”

Continued in part III.