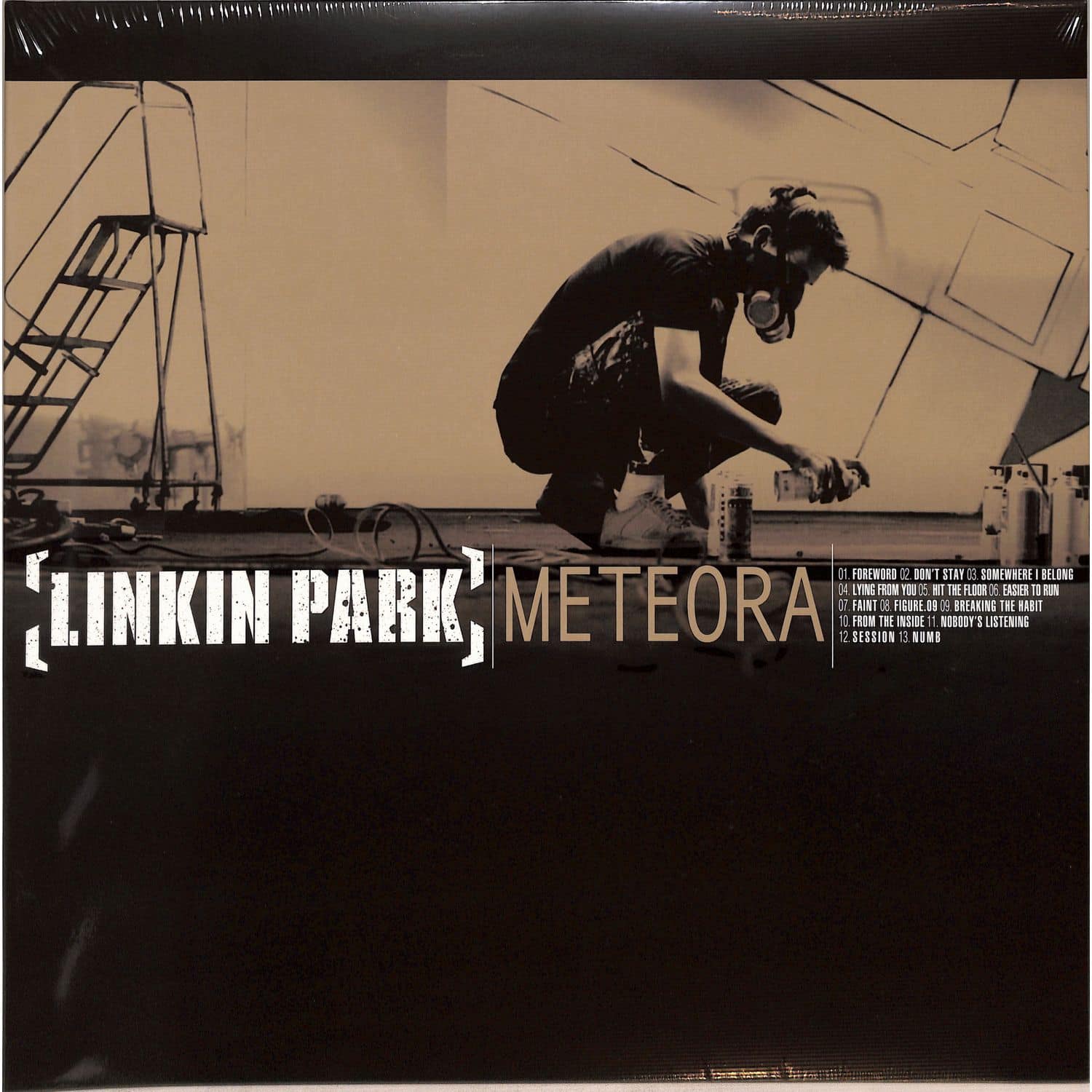

Nu-metal is exceedingly naff – this much is clear. But there’s no room for musical snobbery here at Drunkenness and Cruelty, where the likes of Neil Young and Bob Dylan are derided as insufferable and overrated Baby Boomer boner-bringing bores, whereas Madonna and Britney Spears are rightly celebrated as the pop messiahs that they undeniably are. And the fact is, there’s no escaping the cultural import or impact of nu-metal in the early 2000s, and so there is – for better or worse – no way of avoiding an in-depth reckoning with one of the genre’s most commercially successfully records, by the genre’s undisputably most commercially successful band; Meteora, by the idiotically named Linkin Park.

For the sake of context; my coming-of-age music was mid-90s alternative rock like Nine Inch Nails, Marilyn Manson, the Smashing Pumpkins, and Type O Negative. By the time nu-metal hit at the end of the 90s, I was already a gnarled veteran of maladjusted guitar rock, and I’d long since moved on to the lighter, breezier pastures of Britpop and indie music. I distinctly remember being most unimpressed with Linkin Park. For a start, the choruses were rapped by a guy wearing lots of hair gel, and by this point I’d already arrived at the conclusion that any attempt to combine rap and metal à la Korn and Rage Against the Machine was utterly repellent (Faith No More I could forgive, simply because they didn’t seem to take it or anything else very seriously).

Moreover, I found the angsty, but suspiciously clean-cut, lyrics to be contemptible, even borderline comical. Trent Reznor’s inner turmoil struck me as troublingly authentic, and it was articulated with some sophistication and mystery, while Manson’s meditations on contemporary American life appeared to my teenage brain as enormously profound and literate. In retrospect, I would revise those assessments, particularly the latter. But they’re not entirely baseless. Reznor and Manson were both exceedingly smart, believably self-destructive, and indisputably committed to their respective artistic projects.

Linkin Park, by contrast, purveyed angsty rock music for imbeciles, a kind of dumbed down, radio friendly extrapolation of what I grew up with. Above all, they seemed eyebrow-raisingly manufactured, an attempt to turn the juvenile fury of bands like Korn into something more gratifyingly predictable, controllable, digestible, and marketable. Just raucous and discordant enough to be edgy, but not so raucous and discordant that your parents would make you change the channel. To my 18-year-old self, pop metal with rapped choruses and dumbed down Jonathan Davis lyrics appeared as an eminently risible prospect, though I do remember finding the unapologetic accessibility of Linkin Park’s music to be intriguing, to the extent that I actually bought Hybrid Theory, their debut album, mainly on the strength of the singles.

Ironically, of course, Chester Bennington turned out to be the real deal; a genuinely tortured soul who endured some horrifying childhood experiences, whose considerable wellsprings of malcontent were anything but marketing department-induced histrionics, and who, in contrast to some of his more credibly tormented peers, topped himself while still comparatively young. A knowledge of his unhappy fate puts a different slant on listening to Linkin Park’s early, angsty pop-metal records, because, in retrospect, it would appear that Chester was indeed writing about his real experiences, rather than mechanically following the instructions of Warner Bro’s marketing department by trying to conjure a cuddlier version of Korn.

None of which, unfortunately, changes the fact that a sizeable percentage of the content of Meteora comprises indistinguishable, forgettable, and disposable variations of the exact same song. Chester barks over choruses of scything but, of course, impeccably polished guitars, while the verses consist of eerie samples, synths, and Mike Shinoda’s pained, not very dynamic rapping, like a truly Satanic invocation of some unholy hybrid of Layne Staley and Fred Durst. The album comes in at a mere 36 minutes, yet the amount of filler on it is alarming. Almost all of it sounds the same, and each song offers a variation on the same themes of self-hatred and toxic relationships, all the while drawing on consistently cliched and restricted language.

To wit; “Hit the Floor” is about being a loser, baby, so why don’t you kill me; “Easier to Run” is only the five millionth humourless take on addiction in the history of rock music; the unfortunately titled “Nobody’s Listening” tells of a neglected teenager (probably) whose parents, guardians, friends, and other responsible adults ignored the red flags for too long; while a succession of indistinguishable malcontented relationship songs, with titles like “Faint” and “From the Inside”, proffer and speedily exhaust the exact same musical formula and identikit, tormented and embittered lyrics.

But so what? As Kurt Cobain knew, teenage angst pays off well until you get bored and old, and even in 2003, there was absolutely nothing new about rock cynically targeting the prosaic Weltschmerz of greasy teenagers who aren’t very good at sports. But surely it wasn’t always this simplistic. Robert Smith, Morrissey, Layne Staley, even Jonathan Davis had more to their games than this. In terms of musical and lyrical complexity, The Downward Spiral is light years beyond the simpering assemblage of therapy-speak cliches and nu metal-by-numbers knock offs which comprises most of Meteora. For the most part, the song writing is quite simply staggeringly pedestrian.

And yet, the album is not entirely charmless, or irredeemably simple minded. Unexpectedly, there are moments of optimism and resolve amidst the unending (and yet strangely unmoving) rage and self-abnegation. The rapping on “Somewhere I Belong” is intensely grating and reeks of MTV during the Bush administration but, in Chester’s plaintive expression of a desire to heal and grow, there’s slightly more food for thought than on most of the rest of the album. “Breaking the Habit”, meanwhile, is an undoubted banger, one of the few moments where Linkin Park briefly set aside the relentless and migraine-making rock radio guitars, and essay some meaningful lyrics which offer a compelling meditation on the difficulty, but the achievability, of overcoming the compulsion to behave like a toxic, high conflict asshole who “the battles always choose”. Ultimately, it’s a song about increasing the space between stimulus and response, Victor Frankl style.

But insofar as Meteora has a central theme, it’s that old adolescent chestnut of identity: that is, the basic conflict between, on the one hand, Chester’s “authentic self” and, on the other, the pressures and expectations of friends, lovers, and society. To be sure, this doesn’t always make for great music; “Don’t Stay”, “Lying from You”, and “Figure.09” are all punctuated by Chester’s constant complaints that he is compromising his own God-given nature in order to obtain someone else’s approval, and all three are as anodyne as much of the rest of the album. “Numb”, however, is Meteora’s standout moment, Linkin Park’s most anthemic and coherent statement on the importance of setting boundaries and retaining one’s own individuality in the face of the distorting compromises and self-adjustments which inevitably characterise human relationships, especially those of the toxic or abusive variety.

Needless to say, this commentary on the importance of authenticity flies in the face of a long, proud, glammy rock’n’roll tradition which makes precisely the opposite contention, calling into question and even sending up the very idea that we have an “authentic self”, or that the uncovering and realisation of such a self, should it exist, is worth aspiring towards. This second tradition embraces the post-modern chaos of multiple selves, or of no self at all, with a sort of nihilistic irony, like T. Rex, or Queen, or U2 on every album between The Joshua Tree and All That You Can’t Leave Behind.

To be sure, knuckle-dragging metal music isn’t known for its embrace of sardonic, airy-fairy insincerity, but it’s not entirely unheard of either, from Alice Cooper to Marilyn Manson, who transitioned from the gothic S&M of Antichrist Superstar to a space alien with breast implants on Mechanical Animals. Even Limp Bizkit, the band which most resembled Linkin Park in terms of their diabolic combination of rap and metal, were surely taking the piss most of the time, or at least I prefer to believe that they were in order to preserve my sanity.

But Chester Bennington, it seems, was of a more romantic bent than these arch-ironists and cynical chancers, always hoping to recover the dreamlike nirvana of authenticity and the “true self” beneath the searing pain of societal expectation. This perhaps partly explains why he went down with the ship, while his less idealistic contemporaries merely retreated to their Beverley Hills mansions, home gyms, and podcasts – the prosaic philistinism which was always the inevitable and logical fate of the half-witted and profoundly safe petite bourgeois teenage rampage of nu-metal.

* *

Standout tracks: “Somewhere I Belong”, “Breaking the Habit”, “Numb”