Just to nail my colours to the mast; I don’t like prog rock, I find its overly long, meandering song structures and autistic twenty-something-never-felt-the-touch-of-a-woman lyrics about warlocks and the moon landing to be contemptible and laughable, and also offensive to my pop sensibility, need for concision and melody, and sub-clinical Attention Deficit Disorder. But what this really comes down to is my frank aversion to music nerds, the aforementioned, overwhelmingly male, frequently virginal dullards who produce their unwashed manhoods at the mere mention of terms such as “signature change” and “chord progression”.

If you want my opinion, music is not about “technical skill”; it’s about bringing together spirit, emotion, and the intellect to produce an artistic statement or some kind of transcendental experience, or at least entertainment, and preferably one with the broadest potential for facilitating a connection to as many people as possible (or, if we’re being cynical, for shifting lots of units and making lots of money). But self-congratulatorily “neurodivergent” music nerds approach music like a sport – how fast someone can move their hands up and down a fretboard, an eerie incantation of the self-pleasuring that life has cruelly restricted them to – or worse, they approach it like engineering, constructing things mechanically and “innovatively”, with scant regard to melody or the underlying sensuality that makes for great rock.

Long-haired male brains-in-jars moving their hands very fast and in unconventional ways around a guitar, singing about a Carl Sagan book they read while stoned, is my idea of rich material for a satirical film about the 1970s music scene, but it doesn’t make for good music. Which brings us to Rush, a Canadian prog rock band formed in the 1970s, who I’m only aware of because they are adored by Nicky Wire, the bassist and lyricist of the Manic Street Preachers, one of my favourite groups when I was growing up. The Manics are not very prog; they are inveterate chasers of mainstream success, and even now, in their mid-50s, they are still gamely and tiresomely producing 4-minute “world-beating” radio anthems for Britain’s saintly and sacred NHS workers, peace be upon them. But Nicky goes on about Rush so often that I finally felt compelled to check them out.

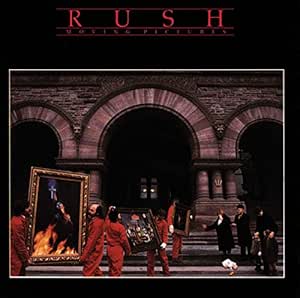

Of course, there’s no way I could go full prog and listen to some of Rush’s mid-70s albums, which consisted of 10-minute, 12-part marathons with subtitles such as “Cygnus (Bringer of Balance)” and “The Ghost of the Aragon”, for fear that I’d never again be able to make eye-contact with an adult female. But Moving Pictures is commonly considered one of their more accessible records, where they – to some extent – reined in their prog instincts and reduced the length of the songs to a mere five or six, rather than ten or twelve torturous, minutes.

But that’s not to suggest that the music is any more listenable merely because it’s more concise. It sounds like a high-tech Led Zeppelin, which is not intended as a compliment, as the three people who read my review of Led Zeppelin IV will know. The production is beautifully clean; Geddy Lee’s shrieky, hysterical voice is prominent; and there are some space-age synths and sound effects to remind us that it’s not 1970 anymore. But the focus is very much on the guitar, on the “sick riffing”, on the crunch and cacophony. Emotionally immediate melodies and rousing choruses are conspicuous by their absence, which for me, a pop afficionado, is utterly unforgivable, and once again, constitutes a remorseless contravention of the fundamental sensuality that music should tap into.

Lyrically, it’s more of a mixed bag. In a most unusual twist, Rush’s scribe, Neil Peart, was also their drummer. He apparently “always had his head in a book”, and was the only member of the band capable of rendering his thoughts as singable – or at least shriekable – words. He deserves some credit, because a sizeable percentage of 70s rockers were uninterested in and absolutely terrible at writing lyrics, being more interested in “riffing” on their replacement phalluses. To this day, a lot of rock lyrics, even by some of my favourite bands, are mushy, meaningless, stream of consciousness, that-word-sounds-good-here garbage. Neil Peart’s lyrics are stark, considered, and coherent, but frequently, in my opinion, a little gauche, and quite obviously born of the brain of a highly intelligent manchild.

“Tom Sawyer”, Moving Picture’s most recognisable song, is a case in point. It has all of the ingredients I’ve already described – a dramatic, electronic, Star Trek-style intro, crunching riffs, and a Robert Plant-style shriek, with some well-formulated but slightly cringey lyrics about a modern-day man’s man; quietly reserved, stoic, and not easily influenced by, say, the inveterate killjoys of the Deep State. Basically, the kind of thing that unfortunate tech bros who listen to tiresome podcasts about “neo-masculinity” might misinterpret as a personal anthem.

“Red Barchetta” is also straight from the mancave – based on a science fiction story about a “dystopian” future where, shock horror, motor cars have been banned and replaced by safe, environmentally friendly modes of transport, pleasing to mothers of young children and Liberal Democrat voters, but perhaps not to aspiring Elon Musks. In the song, our protagonist secretly heads out to his uncle’s farm to race an old red Barchetta around, and to assert his need for (harmless) masculine thrill-seeking in the face of the Stalinist Nanny State’s incessant interference.

In time-honoured fashion, other songs on Moving Pictures moan about the pressures of fame and the debasing effect of commercialisation on art. This is a remarkably common leitmotif of prog rock – it’s a dead horse that Rush themselves already beat on “The Spirit of Radio”, while Marillion and King Crimson subjected their listeners to similar whinging with “Incommunicado” and “The Great Deceiver”, respectively. It stands to reason that the philosopher-kings of progressive rock would take great exception to anything that threatened to intrude on the sanctity of their ivory towers, like signing autographs. But anyway, “Limelight” is an – admittedly enjoyable – slice of, well, 80s hair metal about how Neil Peart “can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend”, and in which he implores himself to focus on the “underlying theme” – presumably, artistic creation – rather than getting too depressed about everyone wanting to interview him. “Vital Signs”, the album closer, is more about being knackered and on tour, but it’s musically less interesting than “Limelight”.

Mortifyingly, Rush also condescend to embark on some ill-considered social critique. “The Camera Eye” is where their desire to bore the listener to death and showcase their dexterity gets the better of them – the song clocks in at 11 minutes – but the lyrics are an interesting take on another familiar rock theme; the decadence and promise of city life. To their credit, Rush neither come down on the pastoral-environmentalist side of the divide (like the Kinks), nor do they opt for a seedy and nihilistic celebration of urban anonymity and opportunity (as on Guns ‘N Roses’ “Welcome to the Jungle” or, come to think of it, Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature”). Instead, they merely take note of the “possibilities”, but also the “hard realities”, of the conurbation. “Witch Hunt”, meanwhile, is most topical; a dark warning of book-burning, immigrant- and weirdo-hating moral majorities, although once again, the lyrics are well-crafted, but perhaps a little too obvious.

And all the while, the songs sound like backing music from the 1986 Transformers animated movie – though this is perhaps to do a disservice to the emotional immediacy that Vince DiCola was able to invoke on, for example, the superb “Megatron Must Be Stopped”. But on a serious note, I don’t accept that hard rock necessarily has to eschew melody. Just off the top of my head, Guns ‘N Roses’ “Night Train”, Metallica’s “Enter Sandman”, or Marilyn Manson’s “Beautiful People” are tunes, danceable and hummable, despite also sounding raucous, savage, vicious. Indeed, Rush themselves were more than capable of writing melodies (the brilliant “Ghost of a Chance” from 1991’s Roll the Bones springs to mind). Moving Pictures doesn’t raise my ire to the same extent as Led Zeppelin IV, partly because the production is so pristine, the hard-rock crunch is broken with some well-positioned synths, and there’s a lot more depth to the lyrics. But the “signature changes” and guitar virtuosity leave me cold, put it that way.

Overall Rating: * * *

Standout tracks: “Tom Sawyer”, “Limelight”