I saw Simple Minds live in 2015, in the German city of Kassel, and the memory of it haunts me to this day. The audience consisted predominantly of middle-aged Volvo drivers, all of whom were on their feet, jiving and wobbling their sizeable paunches to a succession of watery trans-Atlantic synthpop hits which, as soon as I hear them, instantly transport me back to the unutterably depressing early 90s, especially “Alive and Kicking”, the introductory music to Sky TV’s coverage of the first borderline-unwatchable season of the Premier League. In terms of sheer naffness, that Simple Minds gig was surpassed only by the seminal experience of watching Mike and the Mechanics live in 2013, when they were fronted by mid-90s one-hit-wonder Roachford, a demonic and mercifully short-lived apparition responsible for the epoch-definingly awful “Cuddly Toy.”

That abomination was also a slice of shrill, jarring, mid-90s stadium rock – precisely the kind of fayre that Simple Minds themselves were purveying at the time. So imagine my shock when I discovered, many years after seeing them live, that this apparent incarnation of the embarrassing early 90s new wave hangover, this Simply Red with synths, actually started out as a strange Glaswegian arthouse band influenced by Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream. I remember buying Reel to Reel Cacophony, which astonishingly was released a mere five months after Unknown Pleasures, and being utterly perplexed by what I heard; the coldest, iciest, most inhuman and commercially unappealing Krautrock this side of Der Mensch-Maschine. Was this really the same Jim Kerr that I had been exposed to in Kassel, the cringey mid-life crisis-bedevilled dad, busting his appalling moves to mass titillation at the High School disco, all while wheezing the theme tune to The Breakfast Club?

Well, yes, apparently it was. And yet, as I’ve subsequently discovered, there was a phase of Simple Minds’ career that was even more notable than either their early incarnation as Bowie in Berlin-style post-punks, or their later, baleful embodiment of early-90s dadrock. For in between these two alarmingly disparate versions of the band came the sweet spot of the mid-1980s, when Simple Minds were the primary purveyors – and, arguably, the progenitors – of a kind of euphoric, though still ambient and ethereal, iteration of synth rock.

The impulse behind their switch in style was, of course, financial. After four artsy, underperforming albums, Simple Minds needed to get some songs on the radio and make money. Ten-minute-long Krautrock marathons overlaid with Nikolai Gogol quotes of the kind which punctuated their 1980 album Empires and Dance were apparently not germane to that particular end. So they knuckled down, wrote some snappy pop hits, got on the radio, and sold loads of records, all the while pioneering a new, enormously influential sound – though perhaps, in retrospect, a little too influential for Jim Kerr’s tastes, given that its defining and most commercially successful conjuring was essayed not by Simple Minds themselves, but by U2 on The Unforgettable Fire.

Invoking U2 here is relevant because, just as Simple Minds provided the blueprint for The Unforgettable Fire’s hazy, euphoric combination of rock, synths, and spectral, indistinct, but stirring vocals, so too is there something incipiently evangelical about New Gold Dream. My essential point on the review of The Joshua Tree was that it’s basically Christian rock – not proselytising and in your face like, say, Creed, but subtly infused with biblical themes and images and, above all, powered by an ecstatic, almost messianic sound that can only be adequately described as Christian, but more specifically as evangelical, with its unceasingly uplifting themes of rebirth, eternal life, and a loving God who does not necessarily want to fuck us up for his own amusement, like in Ancient Greece or the Old Testament.

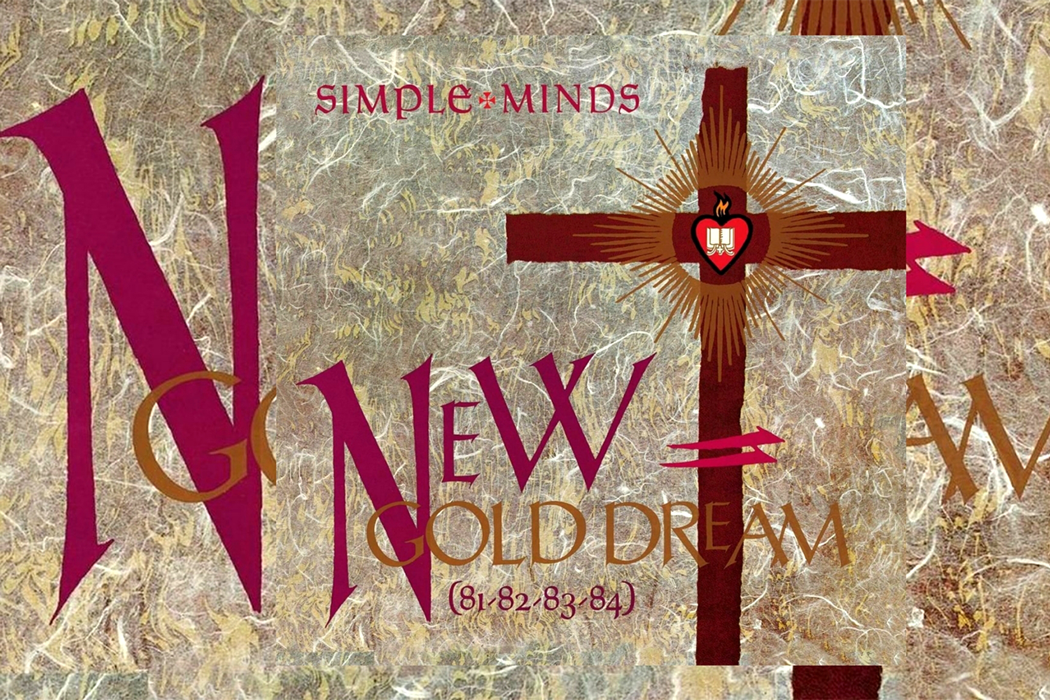

It’s no accident that there’s an actual crucifix on the album’s cover, and indeed, it’s all there in the title of the first single, “Promised You a Miracle” which, on reflection, is not so much jubilant as skittishly manic. Jim Kerr’s singing is oddly inchoate, his vocals a strange ghostly presence in the mix, but the lyrics are full of Pentecostal proclamations about how “everything is possible in the game of life” and “belief is a beauty thing.” The fizzing synths and racing drums of the album’s title track are similarly infused with divine ecstasy, the prototypical Christian leitmotif of rebirth conjured in Jim’s incantation of a “new gold dream”, “crashing beats and fantasy”. “Hunter and Hunted” initially sounds menacing, but like almost everything else on this album, its heart turns out to be benign, its tone uplifting, its references to faith, love, and “heaven being far away” wholly in keeping with New Gold Dream’s essential sacredness. Indeed, even when there are no lyrics, as on the warm and lush instrumental “Somebody Up There Likes You”, the celestial nature of the song’s unspoken message is there in the title.

Sola fide indeed. But as well as glorying in the benevolent will of the Creator, New Gold Dream also finds plenty of time for a more paganistic worship of nature, with references to the weather and natural phenomena peppering the record from start to finish. The opener, “Someone Somewhere in Summertime”, represents a quite brilliant fusion of rhythmic guitar rock and ethereal synths, the perfect introduction to Simple Minds’ newly emerging style, with wistful, exultant lyrics about waking up on “brilliant days” and catching a glimpse of city lights aflicker in the distance. The mysterious and rousing synth song “Big Sleep”, another of the album’s many highlights, takes its nostalgic tale of (presumably) a lost childhood companion, an “immaculate friend”, and suffuses it with references to whirlpools and storms. “Glittering Dream”, meanwhile, is almost as bouncy as “Promised You a Miracle”, and it’s presumably about falling in love, but it too exemplifies this experience with sparse references to lights, the sky, clear days, and midnight.

But with all of that said, the cold, hard truth is that any attempt to prune New Gold Dream for its lyrical leitmotifs is doomed to failure. Most of the time, Jim Kerr’s words make little to no sense. A generous observer might describe them as “cryptic” or “pared down”, but the fact is that they frequently reach Simon Le Bon levels of gibberish, delivering little more than formless, suggestive, stream of consciousness, that-word-sounds-good-here nonsense. For most of the record, this is not just forgivable but commendable, because the mushy words mesh well with the dream-like atmosphere conjured by the music. However, when Simple Minds momentarily desert their compelling proto-dreampop style in favour of the artsy, angular, unapproachable post-punk of their previous albums, the results are discouraging, and the paltriness of the lyrics becomes harder to ignore.

This happens twice on New Gold Dream. “Colours Fly and Catherine Wheel” inexplicably occupies the second spot on the track listing, but the album would have been better served if its interminable, throbbing bassline, ghostly synths, and mumbled lyrics about someone called “Belle” had been relegated to the b-sides. The album’s closer, “King is White and in the Crowd”, is a sinister Joy Division-esque throwback, the only unmistakeably foreboding song on an otherwise thoroughly good-natured album. Its more detailed and expansive lyrics are apparently about the assassination of an Egyptian President but, upon closer examination, they don’t seem to be any more coherent than anything else on the album. Either way, at seven minutes in length, it overstays its welcome, to say the very least.

Normally, two passable songs on a nine-track album would preclude a five-star review. But despite its (relatively) weaker moments, New Gold Dream deserves the full gamut. Seven of its songs are quite brilliant, the sound is groundbreaking and would prove to be enormously influential, and even the two post-punk missteps somehow contribute to the album’s cohesive, dreamlike mien.

All of which raises the question of why U2, who essentially nicked the sound pioneered on this album, ended up playing a residency in Las Vegas while poor old Jim and chums found themselves slogging their gear around Central European backwaters like Kassel. Was it merely because Bono was well positioned to appeal to the US’s jubilantly drunken Irish diaspora, whereas Jim had only stern, pale faced Scottishness to offer? Was it because U2 rooted their artistic transitions in some kind of conceptual and ideological underpinning, as on Achtung Baby, whereas Simple Minds merely chased radio play and grew increasingly soulless in the process? Where Bono and Edge just better songwriters, despite Jim Kerr and Charlie Burchill being the more visionary musicians? Beats me, but what profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his soul? Other than Patsy Kensit.

* * * * *

Standout tracks: “Someone Somewhere in Summertime”, “Big Sleep”, “Hunter and Hunted”